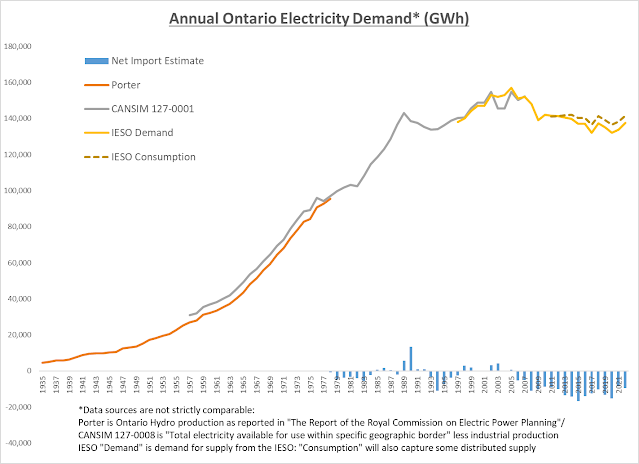

I’ve assembled a long view of annual Ontario Electricity production and/or consumption, from 1935 to 2022. There should be policy implications to take from the data.

Over 12 years ago I published the first article on my first blog: “The Current and Future State of Electricity, as the [Ontario Clean Energy Benefit (OCEB)] comes to Ontario.” I noted in that work that 2010, “[Seemed] like a good time for a big picture overview…” The OCEB was a 10% reduction of bills to, “help consumers manage rising electricity prices for the next five years.” Twelve and half years later the discount has a different name (Ontario Energy Rebate), and is 11.7%. 2023 strikes me a lot like the period running up to the Green Energy Act, so here’s the long view of Ontario’s demand history as information to protect for a repeat of that heist as we renew interest in procuring new sources to meet future provincial demand..The graph of demand for the last 88 years contains 4 data sources, none of which are matched precisely to another:

- “Porter” refers to the chair of 1980’s “The Report of the Royal Commission on Electric Power Planning”, and specifically data contained in appendix A of Volume 2. The figures shown are cited as originating in “Ontario Hydro’s Power Resources Report No. 790201.” In terms of comparison to other data sources in the graph the notable thing about this is that the figures represent production (not demand), and they’re a partial representation of production as there was electricity generated by entities other than Ontario Hydro.

- CANSIM 127-001 is a Statistics Canada monthly dataset built from survey data that existed, at a couple of levels of complexity, from 1957-2007. For purposes of attempting alignment with other data sets, I’ve subtracted from the report’s “Total Available” value the figure shown for “Total Industrial Generation.” Without diving into the exact meaning of the latter field I assume it is self-generated (or behind-the-fence) generation which, while nice to know, is not a component of the other data sets in the chart. It must also be noted “Total Available” includes imports and excludes exports, unlike the “Porter” data

- “IESO Demand” is the figure reported by the Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) as “Ontario Demand” - by which I understand they mean demand for supply from the IESO-controlled Grid (ICG). This differs from CANSIM 127-001 in a couple of ways: it will not capture generation from generators embedded within local distribution companies’ grids but it is data based on data far more reliable that that collected through surveying

- “IESO Consumption”is a figure from the calculation of global adjustment charges as that proportional chargeback tool (for costs of supply not recovered through market revenue) requires calculating a consumers usage as a share of all consumers’ usage. As confusing as that sounds, this measure essentially differs from Ontario Demand in that it does capture the impact of distributed generators in supplying demand, although it omits the share of generation that is lost in transmission lines (as does the CANSIM 127-001).

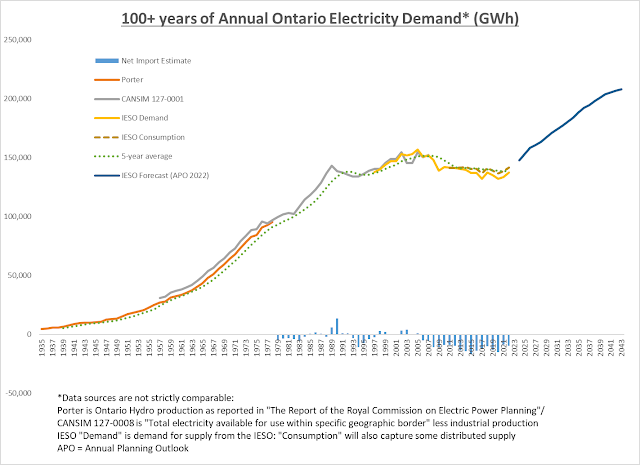

I’ll add the latest demand forecast from the IESO’s 2022 Annual planning Outlook now as it’s currently fashionable to advocate for new construction based on it.

Many passing for experts in 2023 are quite confident that growth will return after 32 years of stagnation. The IESO does make a good case for growth, which they see come mostly in the transportation sector, but also with increases in residential and commercial demand as heating is hoped to move from fossil fuels to electricity. On the other hand, demand in recent years was far below where it was forecast to be a decade earlier.

Over Forecasting demand is a self-preservation mechanism for system planners, perhaps because few observers connect excess capacity with higher bills. There is a risk in doing so - as higher bills can reduce switching electricity for fossil fuels, and even encourage switching from electricity to fossil fuels.

The potential electricity supply being championed today would produce trivial emissions while operating, but have significant up-front capital (and environmental) costs. We’ve suffered high rates due to the introduction of supply twice in the past: once with Darlington’s nuclear sites unluckily entering service during a strong recession, and another AFTER a permanent demand shock in 2009 was ridiculously followed by increased offer rates to attract wind and solar supply.

Over Forecasting demand is a self-preservation mechanism for system planners, perhaps because few observers connect excess capacity with higher bills. There is a risk in doing so - as higher bills can reduce switching electricity for fossil fuels, and even encourage switching from electricity to fossil fuels.

The potential electricity supply being championed today would produce trivial emissions while operating, but have significant up-front capital (and environmental) costs. We’ve suffered high rates due to the introduction of supply twice in the past: once with Darlington’s nuclear sites unluckily entering service during a strong recession, and another AFTER a permanent demand shock in 2009 was ridiculously followed by increased offer rates to attract wind and solar supply.

It's been almost a decade since the province delivered a Long-Term Energy Plan that included a supply category simply called "Planned Flexibility." While the system operator seems to use the term "flexibility" in terms of hour to hour management of the grid, it should also be considered in the planning sense of demand being uncertain. There is an alternative in preparing for a higher demand scenario that is low capital cost - and higher in operating cost. It is natural gas power plants, and it is, in my opinion, dangerous to advocate banning such plants prior to significantly higher demand occurring, and significant value improvements in alternatives for low capacity factor, high capacity value, peaking resources become obvious.

4B9DEE7FC3

ReplyDeleteBeğeni Satın Al

Ucuz Takipçi

Bot Takipçi Atma